Civil Funeral Ceremonies and the story of Two Sisters

by Mark O'Connor - Poet, Celebrant, Writer and Broadcaster - 22/11/07

by Mark O'Connor - Poet, Celebrant, Writer and Broadcaster - 22/11/07

mark@Australianpoet.com : Phone: (+61) 2 6247 3341 or (+61)451 517 966

: www.australianpoet.com : twitter - @Australian_poet

The general issue is this:

As Moira Rayner puts it:

When someone you love dies, society expects you to arrange two things:

a ceremony or rite of passage to honour the deceased person;

and the dignified disposal of their body.

The ceremony is the most important part -- that is what is remembered, and begins the healing. The ceremony is usually performed by a celebrant or a member of the clergy. The dignified disposal of the body is a funeral director’s job.

But it's the funeral directors who are running the show.

Reforms introduced when Lionel Murphy was Attorney General finally broke the near-monopoly of the clergy upon weddings and funerals. The clergy had been offering one-size-fits-all wedding and funeral ceremonies (albeit with beautiful words from the King James bible etc.)

These ceremonies were not about the particular individuals they supposedly celebrated or commemorated. They were about the Churches' understandings of the sacrament of marriage or of the fact that a soul had gone to heaven or hell. Non-believers were required to pretend to become temporary Christians for weddings and funerals, or else to put up with insultingly perfunctory registry office weddings or "unbelievers' funerals".

Instead civil celebrants began showing people how they could devise ceremonies with words and rituals that were about themselves (or about their dead friends) as individuals. The Churches were forced to compete, and today most of them allow personalised marriages and funerals, though sometimes grudgingly. Australia leads the world in the civil celebrancy movement, and about 63% of marriages are civil ceremonies. (Britain for instance lags far behind.)

It is even more important that there should be personalised funeral ceremonies — ones that really speak about the person who has died and thus help start the healing process. (Most couples with a healthy relationship will only laugh if something goes wrong at their wedding ceremony; but a funeral ceremony that miscues can leave relatives, and especially orphaned children, with unspoken/unrecognised griefs dangerously bottled up inside them.)

Yet today it is only civil marriages that are in a healthy state. Funerals are not. The funeral parlours are driving quality celebrants out of the business, and offering funerals with expensive coffins and premises but only perfunctory or generic ceremonies.

The funeral directors' trump card has been that they control the bureaucratic process that creates a proper registration of a death.

I can best explain to you how they use this power by describing a typical event in which I was recently a fly on the wall.

The Two sisters and the Celebrant Funeral

Two sisters who have spent years looking after their elderly mother are looking for a funeral parlour/director to arrange her burial. They are pre-occupied with having the body picked up — since the hospital will only release it to a recognised funeral firm. They have little money, and they have been told that they need to be businesslike. "Get at least three quotes, and compare prices and quality."

So they go into the first funeral parlour and tell the receptionist that they just want a quote. The receptionist says, "Certainly! The director will be here in a minute. But first we'll need some basic info. from you. If you wouldn't mind filling in this form ..."

The sisters oblige — and are trapped. The form they are filling in is not really relevant to the quote. It is the information required for disposal of a body, and the form requires them to establish a number of facts about the dead person's identity and history, starting with date and place of birth ... The receptionist helps them through the complications of the form. Since she is helping them to talk about the person who has absorbed all their attention and energy of late, they feel the receptionist's involvement as friendly attention, and as proof that this is a caring firm.

By the time the form is finished, 40 minutes have evaporated. They are on their second cup of tea; and there is no longer any question of their moving on to two or three other funeral parlours for rival quotes. At this point the receptionist's reluctance to discuss prices evaporates (along with her need to consult the absent director).

She takes them through the three big ticket items:

They will need to pay so many thousands of dollars for a suitable burial plot; so many thousands for the firm's services (including their decorous premises and staff, removal and preparation of the body, etc); and finally even more thousands for the coffin.

She shows them a series of coffins that are really far too expensive for them; but because the sisters have failed to agree in advance on how much they would spend on a coffin (in fact had formed only a hazy idea of what the items and expenses would be) they are easily divided and put under pressure. No one wants to be told later, "Well you were the one who wanted to shove Mum into the ground in the cheapest coffin we could buy!" And no other way of expressing their love for their mother has been proposed to them. So they both say they don't like the color of the most expensive coffin, but then pretend enthusiasm for another whose price is only a little less out of their range.

At the end, almost as an after-thought, the "receptionist" says: "You mentioned your mother was once an Anglican. I could arrange for Fr McKenzie from the local Anglican church to do the service. He doesn't insist on payment, but I think you should make him an 'offering' of $180 dollars."

The sisters are so relieved to find this will not be another huge expense that they readily agree — hardly noticing that they have spent most of their money on a lump of rainforest timber that will be briefly glimpsed then slide into the ground for ever, and almost nothing on the service that should have commemorated their mother.

Of course, for so small a fee, Fr McKenzie could afford to do little more than open up his church, perform a standard ceremony (hopefully pronouncing the dead person's name correctly) and then go out to the grave-site to perform the final (equally generic) committal.

This is what happens in thousands of cases, and relatives are understandably disappointed. In this case things turned out better. The dead woman was my mother-in-law and I am a qualified (though very part-time) civil celebrant. So at this point I stepped in.

I first established that the Anglican priest was prepared to have a "eulogy" inserted into his ceremony, provided he didn't have to write it or deliver it. I then spent a couple of days assembling the story of this shy woman's fascinating and somewhat secretive life, collecting not just the facts but also the anecdotes that best brought our her humanity and the way it had felt to lead her sort of life.

Then I checked back with the various informants and reconciled disagreements. (Relatives can be very possessive about their differing versions of someone's life.) Then I reworked the information into a speech of the right length that was decorous and appreciative, but also true and a useful piece of history for the family's future historians.

I also made sure it recognised the viewpoints and contributions to her life of those who were there to mourn her. And finally I rehearsed, partly memorised, and delivered the speech. All this was at least ten hours work (though of course I did not charge for it). It would have cost about $1000 dollars (or a fraction of the price of the coffin!) if done professionally.

As this story illustrates, funeral parlours are using their position of power to pay celebrants so little that it becomes extremely difficult for a celebrant who does the job properly to specialise in funeral celebrancy. (As one client told a celebrant recently, "I wouldn't even get out of bed for what I'm paying you to commemorate Dad's life.")

Good and dedicated funeral celebrants commonly practice for a year or so, then just as they have learnt to do it well they give up — because they simply can't cover their time and expenses. There are exceptions.

Some enlightened funeral directors will pay a little more to get a worthwhile celebrant; and there are dedicated celebrants who continue to do the job because they have independent incomes and they know how much people need them.

But the most common pattern is that funeral directors see that there is a limited pool of money to be got out of the families of the deceased, and so they prefer to de-emphasise the ceremony and "eulogy" (on which they don't get a cut) in favor of getting people to spend up big on the coffin and their premises and services.

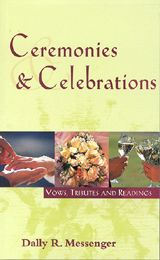

That is why Dally Messenger III (yes, he is the grandson of the footballer, if you're a rugby fan) who is one of the great pioneers of the civil celebrancy movement in Australia has been trying to shake the mould. Yet when he started to press funeral directors to pay celebrants at least $50 more per funeral, some of them dobbed him in to the ACCC.

As Morira Rayner puts it:

Dally Messenger’s life’s work has been to train and improve the quality of funeral celebrants.

On 12 August, Dally agreed to settle civil litigation taken by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) against him and his one-shareholder company in the Federal Court because, at the request of a small group of celebrants, he had signed a letter to Melbourne funeral directors asking them to raise the fixed fee -- their fixed fee -- by $50.

In a mediated settlement he agreed to pay fines and costs of $46,000.

It seems that a body that was meant to control rip-offs came in on the side of the rip-off merchants.

I know Dally Messenger well. He trained me as a civil celebrant; but long before that we were personal friends, and I admired and continue to admire his integrity and altruism. If the media ran this story they could use his case as the peg on which to hang their story. Messenger would be a most credible and articulate witness as to what has been going on in the funeral industry. Of course the media would have to have to check whether his "mediated settlement" allowed him to appear on camera.

Even if he couldn't be involved, I and many others know what's what in that area (I almost said, "we know where the bodies are buried"!) and could gather some articulate witnesses and some very impressive human beings.

This report is not just another dispiriting tale of how bad the world can be. Ventilating this issue could quite largely solve the problem. Once people realise that the way to have your relatives commemorated properly is to ask around, select a good celebrant (preferably one you've previously seen in action), and hire them separately from the funeral director, the standard of funerals in Australia can rise just as the standard of marriages has.

Mark O'Connor

Ceremonies - all |

History |

Marriage Ceremonies |

---=